El verdadero significado del GUERNICA

ART ESP / ING

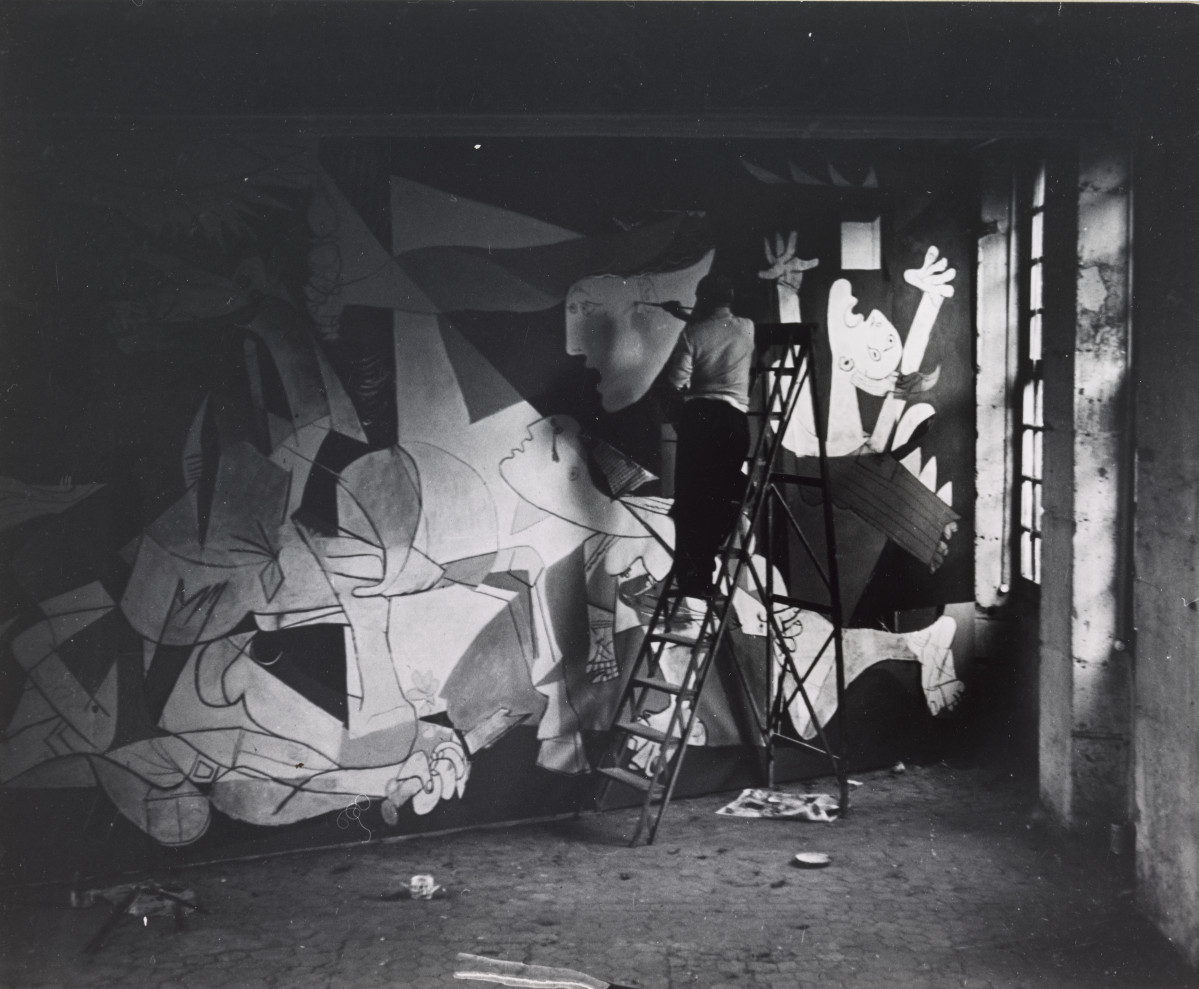

Nos adentramos hoy en un análisis profundo y controvertido de una de las obras más emblemáticas del siglo XX: el Guernica de Pablo Picasso. Desde la perspectiva que modestamente represento como Dr. José M. Castelo-Appleton, nos proponemos desentrañar una hipótesis que, aunque desafía la narrativa dominante, merece ser examinada con rigor y mente abierta. El arte, en su esencia más pura, no debería politizarse.

Por desgracia, esta politización ha sido una constante a lo largo de la historia, una tendencia que a menudo desvirtúa la intención original del artista y el mensaje intrínseco de la obra para ajustarse a agendas ideológicas. Este artículo invita a la reflexión sobre la génesis de esta pintura monumental, sugiriendo una conexión con eventos y figuras que, si bien son fundamentales para la historia cultural española, rara vez se asocian directamente con la interpretación canónica del Guernica. Nuestro objetivo es fomentar un debate informado y estimular nuevas líneas de investigación sobre el verdadero significado y la inspiración original de esta pieza.

El Ocaso de una Época Luminosa: La Edad de Plata y el Destino de Ignacio Sánchez Mejías

La historiografía cultural española a menudo sitúa el inicio de la Edad de Plata – ese período de efervescencia intelectual y artística que precede a la Guerra Civil – en torno a 1920. Pero, para aquellos que observan los hilos invisibles que conectan los grandes eventos con los destinos individuales, su génesis simbólica puede rastrearse hasta un suceso trágico y personal: el fallecimiento de Joselito "El Gallo". El 16 de mayo de 1920, en la enfermería de Talavera de la Reina, la escena es desgarradora: Ignacio Sánchez Mejías sostiene la cabeza inerte de su cuñado Joselito, el “Rey de los Toreros”, que había sucumbido a la cornada del toro Bailaor. Aquel instante no solo marcó el fin de una era en la tauromaquia, sino que también, como si de un presagio se tratara, selló el destino del propio Ignacio, una figura destinada a ser nexo entre la tradición y la vanguardia.

Aquellos tres lustros luminosos que definieron la Edad de Plata no solo fueron testigos de la consolidación de la Generación del 27, con la que Sánchez Mejías mantuvo lazos profundos, sino también de una explosión creativa en todos los ámbitos. Sin embargo, su final simbólico, trágico y poético a la vez, se materializó el 11 de agosto de 1934. En un traslado agónico desde Manzanares a Madrid, el propio Ignacio, herido de muerte, remontaba una carretera andaluza polvorienta, asolada por el sol abrasador y, más ominosamente, apestada por la misma gangrena que reptaba por sus muslos. Se estaba sentenciando no solo la vida de un hombre extraordinario, sino toda una época; mientras sus medias rosas se empapaban con la sangre derramada, se escribía el epitafio de una era de esplendor.

La trayectoria de este polifacético matador, intelectual, dramaturgo y mecenas, es una pieza indispensable para comprender la efervescencia artística y cultural de la década fundamental de los años 20. Menos de dos días después de aquel viaje terrible, llegaba el fin irremediable de aquel “andaluz tan claro, tan rico de aventura”, que quedaría inmortalizado, con la maestría que solo la poesía puede lograr, en el lamento eterno del poemario de Federico García Lorca. La muerte de Ignacio no fue un mero suceso taurino; fue un cataclismo cultural que resonó en los círculos intelectuales y artísticos de España, y es en esta resonancia donde, quizás, se encuentra una clave oculta para desvelar el Guernica.

Para entender la magnitud de su partida, es crucial hacer un ejercicio de memoria y contexto. Ignacio Sánchez Mejías había regresado a los ruedos a la edad de 43 años. Aunque se rumoreaba que lo hacía por aburrimiento, la única verdad palpable es que su destino, trágico y glorioso, ya estaba escrito. Aquel 11 de agosto de 1934, el matador ni siquiera estaba anunciado en Manzanares. Acudió a la carrera, sin su propia cuadrilla, tras un accidentado viaje desde Huesca. Había aceptado la sustitución de Domingo Ortega, quien había sufrido un percance menor. Cuando iniciaba la faena al toro Granadino, marcado con el hierro de Ayala, sufrió una profunda cornada en el muslo. Su negativa a ser operado en la modesta enfermería del coso manchego, exigiendo su traslado a Madrid para ser intervenido por médicos de su confianza, selló su destino. Las circunstancias del penoso y largo viaje acabaron desencadenando la gangrena. No había vuelta atrás. Ignacio falleció el 13 de agosto, exactamente 14 años después de la muerte de su cuñado Joselito, a quien había sostenido la cabeza yerta en Talavera de la Reina. Esta fatal coincidencia de fechas y circunstancias, este eco trágico entre dos figuras centrales de la tauromaquia y la cultura, es un elemento que rara vez se considera en el análisis del Guernica, pero que, como veremos, podría ser fundamental.

El Guernica: ¿Un Lamento Taurino Oculto Bajo el Velo de la Guerra?

Llegados a este punto, resulta imperativo formular un par de preguntas que desafían el dogma establecido: ¿Estaba el cuadro Guernica ya pintado, o al menos conceptualizado, cuando se produjo el trágico bombardeo de la ciudad vasca el 26 de abril de 1937? ¿Se le cambió el nombre y la narrativa tras la incursión aérea de la Legión Cóndor, adaptándolo a un evento de mayor calado político y mediático? Para muchos, estas cuestiones pueden sonar a herejía. Sin embargo, en el ámbito de la crítica de arte y la historia, ninguna verdad debe ser inmutable si nuevas perspectivas y evidencias pueden arrojar luz sobre ella.

Desde nuestra visión, todo esto, a estas alturas, parece irrefutable. Pero también podría serlo que el origen de la obra, en realidad, deba enmarcarse dentro de la ola de luto cultural y social que siguió a la muerte de Ignacio Sánchez Mejías, de la que –posiblemente– tampoco se escapó la sensibilidad de Pablo Picasso. No es descabellado pensar que el estallido de la Guerra Civil Española, el encargo apremiante del gobierno republicano –por el cual el pintor cobró una sustanciosa suma de 150.000 francos franceses, un factor no menor en la vida de cualquier artista– y la oportunidad que se abría para seguir aumentando su ya considerable notoriedad internacional, pudieron haber hecho el resto. ¿Oportunismo? ¿Afán de protagonismo? Estas son preguntas incómodas, pero legítimas en el análisis de cualquier obra de arte, especialmente cuando se entrelazan con la política y las finanzas. La posibilidad de que Picasso, consciente de la resonancia emocional que la tragedia de Guernica provocaba a nivel mundial, adaptara una obra ya en proceso para darle un nuevo y potente significado político, es una hipótesis que merece nuestra atención.

Nosotros hemos tenido acceso a diversas opiniones y versiones que respaldan firmemente la hipótesis de que la génesis del famoso cuadro no tendría nada que ver con la tragedia bélica de Guernica. Esta corriente de pensamiento sostiene que Picasso, en realidad, se habría sumado en un principio a la ola de lamento cultural que siguió a la trágica muerte de Ignacio Sánchez Mejías. El impacto del fallecimiento de Ignacio fue tal que se movió, como pez en el agua, en todos los estratos de la sociedad y la cultura de los años 20 y primeros 30, trascendiendo el ámbito taurino para permear el literario, el artístico y el intelectual.

El renombrado escritor Aquilino Duque es uno de los intelectuales que corroboran esta corriente de opinión, al afirmar con contundencia que la obra “no es más que una adaptación con ánimo de lucro del cuadro, collage, cartón, cartel o como quiera llamarse con el que el artista pretendió sumarse al luto nacional por Ignacio Sánchez Mejías”. Esta afirmación, lejos de ser una conjetura aislada, encuentra eco en la opinión de otros escritores e investigadores de gran reputación, como Francisco Aguado, autorizado biógrafo de Joselito "El Gallo", o el tratadista e investigador malagueño José Morente, cuya erudición en la tauromaquia y el arte picassiano le otorgan una autoridad considerable en este debate.

Iconografía y Símbolos: La Tauromaquia como Clave Interpretativa

La argumentación de estos estudiosos se centra en una relectura de los elementos visuales que componen el Guernica, liberándolos de la carga simbólica impuesta por la narrativa bélica y devolviéndoles su posible significado original dentro del universo picassiano, tan profundamente impregnado de la tauromaquia.

"Un bombardeo es un bombardeo y una guerra es una guerra y este cuadro no representa, se mire como se mire, ni una guerra ni, mucho menos, un bombardeo", afirma el escritor malagueño José Morente. Él se decanta por la tesis de que “el toro representa a un toro y el caballo a un caballo; que la apenada madre con su hijo es una apenada madre con hijo y la dolida mujer de la derecha es simplemente una mujer dolida, por más señas, la amante. La bombilla es una bombilla (de enfermería) y el quinqué, un quinqué. Y el torero que yace en la arena con su estoque roto es el mismo diestro que murió en Manzanares porque no quería que su hijo José Ignacio fuese torero y partiese, una vez más, el ya cansado corazón de su madre, Lola Gómez Ortega, hermana de Gallito, al que ya había despedido 14 años antes”.

Esta interpretación ofrece una coherencia interna asombrosa. Si asumimos que la obra es un lamento taurino, los elementos visuales adquieren una nueva y poderosa significación. El toro, lejos de ser un símbolo de la brutalidad fascista, recupera su papel central en la tauromaquia, encarnando la fuerza de la naturaleza y el destino. El caballo, herido de muerte, podría ser el caballo del picador, una figura recurrente en la iconografía taurina que a menudo sufre las consecuencias más cruentas de la lidia. La mujer que sostiene a su hijo muerto no sería necesariamente una víctima de la guerra, sino una Dolorosa, la madre sufriente que ha perdido a su vástago, una figura universal de luto que resuena con la tragedia de Lola Gómez Ortega, la madre de Ignacio y hermana de Joselito, quien vio partir a dos de sus hijos al ruedo de la muerte.

La bombilla y el quinqué, a menudo interpretados como un sol o un ojo divino que todo lo ve en el contexto de la guerra, podrían ser, como sugiere Morente, elementos prosaicos pero esenciales de una enfermería taurina, el lugar donde tantos toreros, incluido Ignacio, encontraron su fin o lucharon por su vida. Y, crucialmente, la figura del torero que yace en la arena con su estoque roto se convierte en el epicentro de esta narrativa alternativa: el propio Ignacio Sánchez Mejías, tendido en su agonía. El estoque roto simboliza no solo la interrupción de su faena, sino también el quiebre de una vida, de una carrera brillante, y, quizás, el colapso de toda una era.

José Morente también nos recuerda la habitual y profunda inspiración picassiana en el mundo de la Tauromaquia. Picasso, a lo largo de su carrera, produjo innumerables obras con temática taurina, desde bocetos hasta grabados y pinturas complejas. Para él, el toro, el caballo, el torero y la plaza eran más que meros objetos de representación; eran arquetipos de la vida y la muerte, del drama y la pasión. En ese contexto, remacha el investigador, “resulta más lógico suponer que el Guernica es, no una denuncia de la guerra, sino, lisa y llanamente, una obra taurina pues taurino -y mucho- era su autor y taurinos son los elementos (toro, caballo de picador, torero muerto) que pueblan el cuadro”. Esta es una perspectiva que nos obliga a reconsiderar la primacía de la interpretación política y a explorar la posibilidad de un significado más íntimo y personal para el artista.

El Impacto Cultural de una Muerte: Resonancias en la Obra de Picasso

La muerte de Ignacio Sánchez Mejías fue un evento de tal magnitud que no solo conmocionó el mundo de la tauromaquia, sino que se extendió por los círculos literarios y artísticos, impactando profundamente a la Generación del 27. Lorca, Alberti, Gerardo Diego y otros poetas le dedicaron elegías y poemas que inmortalizaron su figura. Picasso, que compartía un profundo interés por la tauromaquia y conocía a Sánchez Mejías (aunque no se documenta una amistad íntima, sí una admiración mutua por el mundo taurino que ambos habitaban de diferentes maneras), no pudo haber sido ajeno a este luto nacional y cultural.

Es plausible, por tanto, que la idea de una gran obra que capturara la esencia de la tragedia, el lamento por una vida excepcional cortada por el destino, estuviera ya germinando en la mente del artista malagueño. Los elementos compositivos y las figuras angustiadas del Guernica podrían haber surgido, en su concepción inicial, de esta resonancia emocional con la muerte de Ignacio, un hombre que personificaba una España culta, valiente y apasionada.

La posterior comisión del gobierno republicano para la Exposición Internacional de París de 1937, en el contexto del bombardeo de Guernica, pudo haber ofrecido a Picasso la oportunidad de revestir una obra ya en desarrollo con un nuevo significado. Al añadir o reinterpretar ciertos elementos, la pintura podría haber pasado de ser un lamento por un torero a un grito universal contra la barbarie de la guerra. Esto no restaría mérito a la genialidad de Picasso ni a la fuerza de la obra, sino que añadiría una capa de complejidad a su génesis, revelando un proceso creativo más dinámico y adaptable de lo que se suele admitir. La posibilidad de una doble lectura, una taurina y una bélica, enriquece el debate y nos invita a mirar más allá de lo evidente.

Un Legado Abierto a Nuevas Interpretaciones

En conclusión, la hipótesis de que el Guernica de Picasso podría tener sus raíces en la trágica muerte de Ignacio Sánchez Mejías, el torero, y su contexto cultural en la Edad de Plata, en lugar de ser exclusivamente una respuesta al bombardeo de Guernica, es una perspectiva que merece ser considerada seriamente. No buscamos desvirtuar la importancia del Guernica como símbolo universal contra la guerra, un papel que ha cumplido y sigue cumpliendo con una potencia innegable. Más bien, proponemos una lectura que enriquece su complejidad y nos invita a reflexionar sobre las múltiples capas de significado que pueden coexistir en una obra de arte.

Los argumentos presentados por estudiosos como Aquilino Duque y José Morente, basados en la iconografía taurina de Picasso y en el impacto cultural de la muerte de Ignacio, abren una ventana a una comprensión más profunda de la obra. La posibilidad de que el artista haya adaptado un concepto preexistente para ajustarlo a un evento histórico crucial, en un momento de gran efervescencia política y personal, es una vía de análisis fascinante.

Me reafirmo que la historia del arte no es una disciplina estática. Las obras maestras, por su propia naturaleza, invitan a la reinterpretación y al debate constante. Al liberar al Guernica de su única lectura posible, abrimos la puerta a nuevas preguntas, a nuevas investigaciones y, en última instancia, a una apreciación aún más rica de la genialidad de Pablo Picasso y del fascinante cruce entre la vida, la muerte, el arte y la historia de España. El legado de Ignacio Sánchez Mejías, ese andaluz tan claro, tan rico de aventura, puede que siga, aun hoy, proyectando su sombra en uno de los lienzos más debatidos de la modernidad. Su vida y su muerte no solo sentenciaron una época, sino que quizás también inspiraron una inmortalidad pictórica.

---------------

We delve today into a profound and controversial analysis of one of the 20th century's most emblematic works: Pablo Picasso's Guernica. From the perspective I modestly represent as Dr. José M. Castelo-Appleton, we propose to unravel a hypothesis that, although challenging the dominant narrative, deserves to be rigorously examined with an open mind. Art, in its purest essence, should not be politicized.

Unfortunately, this politicization has been a constant throughout history, a tendency that often distorts the artist's original intention and the intrinsic message of the work to fit ideological agendas. This article invites reflection on the genesis of this monumental painting, suggesting a connection to events and figures that, while fundamental to Spanish cultural history, are rarely directly associated with the canonical interpretation of Guernica. Our goal is to foster an informed debate and stimulate new lines of research into the true meaning and original inspiration of this piece.

The Twilight of a Luminous Era: The Silver Age and the Fate of Ignacio Sánchez Mejías

Spanish cultural historiography often places the beginning of the Silver Age – that period of intellectual and artistic effervescence preceding the Civil War – around 1920. But, for those who observe the invisible threads connecting grand events with individual destinies, its symbolic genesis can be traced back to a tragic and personal event: the death of Joselito "El Gallo." On May 16, 1920, in the infirmary of Talavera de la Reina, the scene was heartbreaking: Ignacio Sánchez Mejías held the lifeless head of his brother-in-law Joselito, the "King of Bullfighters," who had succumbed to the goring by the bull Bailaor. That instant not only marked the end of an era in bullfighting, but also, as if it were a premonition, sealed the fate of Ignacio himself, a figure destined to be a link between tradition and the avant-garde.

Those three luminous decades that defined the Silver Age not only witnessed the consolidation of the Generation of '27, with whom Sánchez Mejías maintained deep ties, but also an explosion of creativity in all fields. However, its symbolic end, both tragic and poetic, materialized on August 11, 1934. In an agonizing transfer from Manzanares to Madrid, Ignacio himself, mortally wounded, traversed a dusty Andalusian road, scorched by the blazing sun and, more ominously, festering with the same gangrene that crept up the bullfighter's thighs. Not only was the life of an extraordinary man being sentenced, but an entire era; as his pink stockings soaked in his spilled blood, the epitaph of an era of splendor was being written.

The trajectory of this multifaceted bullfighter, intellectual, playwright, and patron, is an indispensable piece for understanding the artistic and cultural effervescence of the fundamental decade of the 1920s. Less than two days after that terrible journey, the irremediable end of that "Andalusian so clear, so rich in adventure" arrived, who would be immortalized, with the mastery that only poetry can achieve, in the eternal lament of Federico García Lorca's poetry collection. Ignacio's death was not merely a bullfighting event; it was a cultural cataclysm that resonated in the intellectual and artistic circles of Spain, and it is in this resonance where, perhaps, a hidden key to unlocking Guernica lies.

To understand the magnitude of his passing, it is crucial to exercise memory and context. Ignacio Sánchez Mejías had returned to the bullrings at the age of 43. Although it was rumored he did so out of boredom, the only tangible truth is that his destiny, tragic and glorious, was already written. On August 11, 1934, the bullfighter was not even announced in Manzanares. He rushed there, without his own cuadrilla, after a troubled journey from Huesca. He had agreed to substitute Domingo Ortega, who had suffered a minor mishap. As he began the faena with the bull Granadino, branded with the Ayala iron, he suffered a deep goring in his thigh. His refusal to be operated on in the modest infirmary of the Manchegan bullring, demanding his transfer to Madrid to be operated on by doctors he trusted, sealed his fate. The circumstances of the painful and long journey eventually led to gangrene. There was no turning back. Ignacio died on August 13, exactly 14 years after the death of his brother-in-law Joselito, whose lifeless head he had held in the infirmary of Talavera de la Reina. This fatal coincidence of dates and circumstances, this tragic echo between two central figures of bullfighting and culture, is an element rarely considered in the analysis of Guernica, but which, as we shall see, could be fundamental.

Guernica: A Hidden Bullfighting Lament Beneath the Veil of War?

At this point, it becomes imperative to ask a couple of questions that challenge established dogma: Was the painting Guernica already painted, or at least conceptualized, when the tragic bombing of the Basque city occurred on April 26, 1937? Was its name and narrative changed after the aerial incursion of the Condor Legion, adapting it to an event of greater political and media significance? For many, these questions may sound like heresy. However, in the field of art criticism and history, no truth should be immutable if new perspectives and evidence can shed light on it.

From our perspective, all of this, at this point, seems irrefutable. But it could also be that the origin of the work, in reality, must be framed within the wave of cultural and social mourning that followed the death of Ignacio Sánchez Mejías, from which – possibly – Pablo Picasso's sensibility also did not escape. It is not unreasonable to think that the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, the urgent commission from the Republican government – for which the painter received a substantial sum of 150,000 French francs, a not insignificant factor in any artist's life – and the opportunity that opened up to further increase his already considerable international notoriety, could have done the rest. Opportunism? A desire for prominence? These are uncomfortable questions, but legitimate in the analysis of any work of art, especially when intertwined with politics and finance. The possibility that Picasso, aware of the emotional resonance that the tragedy of Guernica caused worldwide, adapted a work already in progress to give it a new and powerful political meaning, is a hypothesis that deserves our attention.

We have had access to various opinions and versions that strongly support the hypothesis that the genesis of the famous painting had nothing to do with the war tragedy of Guernica. This school of thought maintains that Picasso, in reality, would have initially joined the wave of cultural lament that followed the tragic death of Ignacio Sánchez Mejías. The impact of Ignacio's passing was such that it moved, like a fish in water, through all strata of society and culture in the 1920s and early 1930s, transcending the bullfighting sphere to permeate the literary, artistic, and intellectual realms.

The renowned writer Aquilino Duque is one of the intellectuals who corroborate this current of opinion, emphatically stating that the work “is nothing more than an adaptation for profit of the painting, collage, cardboard, poster, or whatever you want to call it, with which the artist intended to join the national mourning for Ignacio Sánchez Mejías.” This assertion, far from being an isolated conjecture, echoes the opinion of other highly reputable writers and researchers, such as Francisco Aguado, an authorized biographer of Joselito "El Gallo," or the Malaga-based scholar and researcher José Morente, whose erudition in bullfighting and Picasso's art lends him considerable authority in this debate.

Iconography and Symbols: Bullfighting as an Interpretive Key

The argumentation of these scholars focuses on a re-reading of the visual elements that make up Guernica, freeing them from the symbolic burden imposed by the wartime narrative and restoring their possible original meaning within the Picassoesque universe, so deeply imbued with tauromaquia.

"A bombing is a bombing, and a war is a war, and this painting does not represent, no matter how you look at it, either a war or, much less, a bombing," affirms the Malaga writer José Morente. He leans towards the thesis that “the bull represents a bull, and the horse a horse; that the sorrowful mother with her child is a sorrowful mother with a child, and the grieving woman on the right is simply a grieving woman, specifically, the mistress. The light bulb is a light bulb (from an infirmary), and the oil lamp, an oil lamp. And the bullfighter lying in the sand with his broken sword is the same bullfighter who died in Manzanares because he did not want his son José Ignacio to be a bullfighter and to break, once again, the already weary heart of his mother, Lola Gómez Ortega, Gallito's sister, whom he had already said goodbye to 14 years earlier.”

This interpretation offers astonishing internal consistency. If we assume that the work is a bullfighting lament, the visual elements acquire a new and powerful significance. The bull, far from being a symbol of fascist brutality, regains its central role in bullfighting, embodying the force of nature and destiny. The mortally wounded horse could be the picador's horse, a recurring figure in bullfighting iconography who often suffers the cruellest consequences of the fight. The woman holding her dead child would not necessarily be a war victim, but a Mater Dolorosa, the suffering mother who has lost her offspring, a universal figure of mourning that resonates with the tragedy of Lola Gómez Ortega, Ignacio's mother and Joselito's sister, who saw two of her sons go to their deaths in the bullring.

The light bulb and the oil lamp, often interpreted as a sun or a divine all-seeing eye in the context of war, could be, as Morente suggests, prosaic but essential elements of a bullfighting infirmary, the place where so many bullfighters, including Ignacio, met their end or fought for their lives. And, crucially, the figure of the bullfighter lying in the sand with his broken sword becomes the epicenter of this alternative narrative: Ignacio Sánchez Mejías himself, lying in his agony. The broken sword symbolizes not only the interruption of his faena but also the breaking of a life, of a brilliant career, and, perhaps, the collapse of an entire era.

José Morente also reminds us of Picasso's habitual and profound inspiration in the world of Bullfighting. Throughout his career, Picasso produced countless works with bullfighting themes, from sketches to engravings and complex paintings. For him, the bull, the horse, the bullfighter, and the bullring were more than mere objects of representation; they were archetypes of life and death, of drama and passion. In that context, the researcher emphasizes, “it is more logical to assume that Guernica is not a denunciation of war, but, plainly and simply, a bullfighting work, since its author was a bullfighting enthusiast – and very much so – and bullfighting elements (bull, picador's horse, dead bullfighter) populate the painting.” This is a perspective that forces us to reconsider the primacy of the political interpretation and to explore the possibility of a more intimate and personal meaning for the artist.

The Cultural Impact of a Death: Resonances in Picasso's Work

Ignacio Sánchez Mejías's death was an event of such magnitude that it not only shocked the bullfighting world but also extended through literary and artistic circles, profoundly impacting the Generation of '27. Lorca, Alberti, Gerardo Diego, and other poets dedicated elegies and poems to him that immortalized his figure. Picasso, who shared a deep interest in bullfighting and knew Sánchez Mejías (although an intimate friendship is not documented, there was a mutual admiration for the bullfighting world they both inhabited in different ways), could not have been oblivious to this national and cultural mourning.

It is plausible, therefore, that the idea of a great work that would capture the essence of tragedy, the lament for an exceptional life cut short by fate, was already germinating in the mind of the Malaga-born artist. The compositional elements and the anguished figures of Guernica could have emerged, in their initial conception, from this emotional resonance with Ignacio's death, a man who personified a cultured, brave, and passionate Spain.

The subsequent commission from the Republican government for the 1937 Paris International Exhibition, in the context of the Guernica bombing, could have offered Picasso the opportunity to imbue an already developing work with new meaning. By adding or reinterpreting certain elements, the painting could have transformed from a lament for a bullfighter into a universal cry against the barbarism of war. This would not diminish Picasso's genius or the power of the work, but rather add a layer of complexity to its genesis, revealing a more dynamic and adaptable creative process than is usually admitted. The possibility of a double reading, one bullfighting and one wartime, enriches the debate and invites us to look beyond the obvious.

A Legacy Open to New Interpretations

In conclusion, the hypothesis that Picasso's Guernica might have its roots in the tragic death of Ignacio Sánchez Mejías, the bullfighter, and its cultural context in the Silver Age, instead of being exclusively a response to the bombing of Guernica, is a perspective that deserves serious consideration. We do not seek to diminish the importance of Guernica as a universal symbol against war, a role it has fulfilled and continues to fulfill with undeniable power. Rather, we propose a reading that enriches its complexity and invites us to reflect on the multiple layers of meaning that can coexist in a work of art.

The arguments presented by scholars such as Aquilino Duque and José Morente, based on Picasso's bullfighting iconography and the cultural impact of Ignacio's death, open a window to a deeper understanding of the work. The possibility that the artist adapted a pre-existing concept to fit a crucial historical event, at a time of great political and personal effervescence, is a fascinating avenue of analysis.

I reaffirm that art history is not a static discipline. Masterpieces, by their very nature, invite reinterpretation and constant debate. By freeing Guernica from its sole possible reading, we open the door to new questions, new research, and ultimately, an even richer appreciation of Pablo Picasso's genius and the fascinating intersection of life, death, art, and the history of Spain. The legacy of Ignacio Sánchez Mejías, that Andalusian so clear, so rich in adventure, may still, even today, cast its shadow on one of modernity's most debated canvases. His life and death not only sentenced an era but perhaps also inspired pictorial immortality.